Plain Bagel Congestion Pricing: The Limits of a One-Dimensional Approach

Congestion Pricing Part 1: The Multi-Solving Opportunity and What Stands in the Way

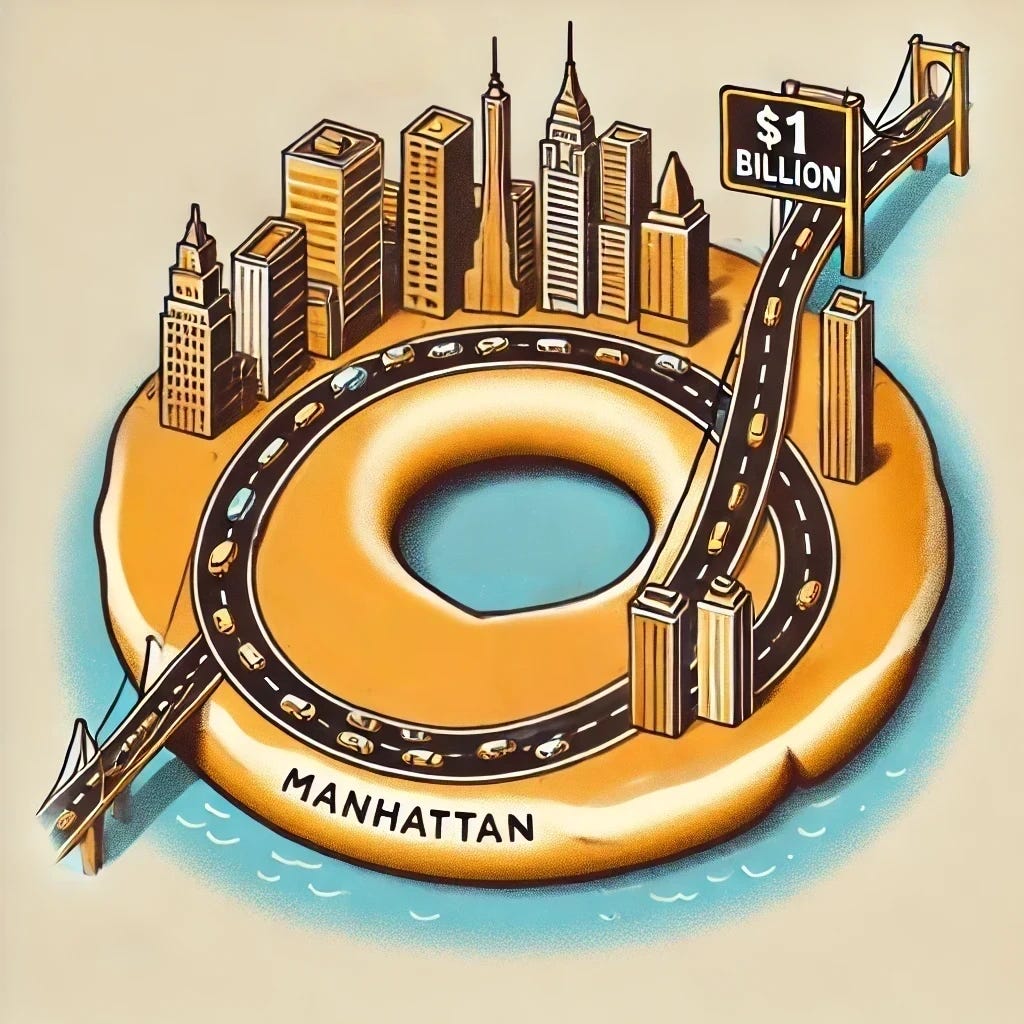

New York has congestion pricing—finally!—and with it, the promise of billions to fund transit. Yet the single-minded political goal of raising $1 billion in revenue risks reaching genuine “congestion relief.” That’s no accident: a tangle of drawn-out reviews, a predetermined infrastructure paradigm, and narrowly framed legislation forced the program into a simple, monolithic design—one that could squander its extraordinary potential to reduce traffic, curb emissions, improve public health, and boost livability.

This post is the first in a short series examining overlooked flaws in New York City’s new Congestion Relief Zone (CRZ), also known as the Central Business District Tolling Program (CBDTP). Let me be clear: I’ve been a dedicated fan of congestion pricing for decades and literally co-founded a road pricing startup to fast-track adoption nationwide. None of what follows should diminish the remarkable achievement of the many advocates, organizations, and agencies who finally brought congestion pricing to life. They deserve our profound gratitude.

But I’m not yet singing from the rooftops celebrating its launch, or early signs of success—because I fear a break-it-all-down President itching to pull the plug. Over this and coming posts, I’ll unpack the structural shortcomings that undermine the scalability of New York’s congestion pricing and stifle its real upside. Let’s start by looking squarely at perhaps the biggest culprit in delays, and silent shaper of policy: the linear, marathon environmental review process.

What Took So Long?

I’m certain that when Andrew Cuomo signed the law enacting congestion pricing in 2019, he pictured himself driving across the congestion boundary in a classic Cadillac convertible, top-down, on a warm summer’s day—perhaps in 2021. Instead, the system launched at midnight in the dead of winter, over five years later, in the waning days of a Biden presidency, without a politician in sight.

There’s plenty of well-placed finger-pointing regarding the delays, with Governor Hochul’s last-minute unexplained scuttling just the latest example. COVID, procedural shenanigans, non-responsiveness from the federal highway administration in the first Trump term, and a brusque, detached, and deposed governor, all played significant roles.

Yet environmental review isn’t receiving nearly enough attention as a villain—it made the entire congestion pricing endeavor more susceptible to delays and political machinations, stretching analysis and approval timelines, and, in many ways, undercutting the breadth of what congestion pricing could accomplish. It forced New York’s program to narrowly focus on a single goal—into a place I call ‘Plain Bagel’ congestion pricing.

'Plain, New York Bagel' Congestion Pricing

There’s a running criticism of blue-state legislators and regulators: they pile on so many requirements on major projects—housing, infrastructure, etc.—that these well-intentioned add-ons become de facto barriers, sabotaging policy goals. Ezra Klein colorfully described this phenomenon as ‘over-seasoning’ in “Everything Bagel Liberalism”.

But that is not what happened with New York’s congestion pricing. If anything, it was kept remarkably plain. True, after Hochul’s pause, leaders and advocates argued that any replacement plan must deliver benefits in three areas—environmental, performance, and financial. Yet only the financial goal is explicitly spelled out in law: generating $15 billion in bondable revenue for the MTA’s capital projects.

Cuomo’s ‘plain bagel’ formula for congestion pricing can be summed up as:

Congestion Pricing System - carve-outs (low-income, accessibility, highways) = $1B/year = $15B bonded

Notice what’s missing: any specific congestion “relief” targets, emissions reductions, or asthma mitigation. Supporters (myself included) often cite the success of similar systems in London, Stockholm, and Singapore, and a smattering of European downtowns, where multiple benefits are realized. But those outcomes are not mandated by New York’s legislation.

I suspect Cuomo, lifetime student and later wielder of New York politics, did this deliberately. He touted the $15 billion rescue for the MTA, threw in carve-outs for accessibility and low-income drivers, differentiated from previous plans with an uncharged roadway around the toll zone, and left it to advocates to raise and praise the broader benefits. It made the politics simpler and, crucially, laid the groundwork for a more straightforward, if not speedy, path through official channels. But by staying so narrow, New York traded away direct congestion relief. Another form of congestion pricing tackles traffic head-on.

The HOT Alternative

Let’s clarify the general theory of congestion pricing: Set a toll so people shift their driving behavior—whether to another travel mode or off-peak hours—and thus reduce congestion. New York uses a fixed, daytime toll ($9 for cars) to accomplish this. Early results are encouraging, but over time, as people experience freer-flowing streets, traffic volumes may rebound, and it’s uncertain whether the long-term reductions will be enough to declare victory over congestion. Meanwhile, the governor is sticking to Cuomo’s narrative: success = collect $1B a year for transit.

High-Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes illustrate a different approach. Instead of explicitly targeting revenue (though they generate plenty), HOT lanes maintain a free-flow speed of around 45 mph by adjusting tolls. If traffic starts bunching up, tolls increase to deter more vehicles; if traffic is light, tolls drop. In other words, pricing achieves a constantly self-regulating corridor.

Of course, complaints about “millionaire lanes” boil up when tolls spike around events or holidays, but experiencing the underlying principle is undeniable: it’s a one-dimensional optimization to keep traffic flowing. Imagine if New York’s big, beautiful toll boundary was similarly designed to explicitly solve for free-flow conditions—revenue for transit would become a happy byproduct.

Uber’s Example—Pricing for Multiple Goals

If HOT lanes target one dimension (speed), Uber targets about fifty. Uber’s “surge pricing” is basically congestion pricing in miniature, except the “corridor” might be any neighborhood where demand exceeds supply. Over the years, Uber has factored in countless data points—driver availability, distances, major events, local weather, even anxious riders’ low phone battery state.

In its earlier days, the Uber app would declare “2.0X Surge” or “3.2X Surge,” explaining exactly how a fare was calculated. Now, calculations are hidden in a black box and riders only see a single, final price. But the underlying workings remain: dynamic, multi-faceted pricing that adjusts in real time. If rider demand spikes, prices go up to entice more drivers into that zone. If traffic is heavy, riders might get a “wait and save” prompt. If EV/Green rides are underutilized, their surcharge is eliminated. There’s no single set price—just continuous iteration across thousands of local markets.

It’s a practical demonstration that pricing can be used to tackle multiple objectives simultaneously—speed, coverage, even emissions. And it raises the question: What if New York multi-solved congestion pricing? Could the State tailor tolls to reduce emissions, improve transit speeds, cut asthma rates all at once—while still raising revenue?

Multi-Solving Congestion Pricing: Dynamic Pricing to Meet Multiple Targets

Imagine a version of congestion pricing that sets not just one goal, like $1B in revenue, but a bundle of targets. I’d suggest:

12 MPH minimum speeds for crosstown buses

Air Quality Index below 80 within the zone

25% of all deliveries occurring at night

And yes, baseline revenue to fund transit

If traffic slows below a certain threshold on major arterials, raise the toll. If air quality monitors detect a spike in pollutants, give a discount to zero-emissions vehicles or ramp up charges on gas guzzlers. If truck routes aren’t shifting enough from rush hour deliveries, credit (or even pay!) fleets for each off-peak trip. These mechanisms don’t need to be perfect at the outset. These measurable traffic, emissions, and public health goals can be responded to automatically.

The technology to handle this is out there—Uber’s algorithmic approach is one example. The real question is why high level discussions never even considered it. That brings me back to the real force keeping these dynamic ideas off the table: environmental review.

Why Aren’t We Doing This Already? Environmental Review

Enter the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the associated Kafkaesque review apparatus, which demands exhaustive analysis whenever a project or policy might significantly impact the environment. There’s plenty that could—and should—be said about how the MTA approached its Environmental Assessment. Agencies of all stripes and their staff tend to be overly cautious, fearing lawsuits and the specter of being singled out for failing to anticipate a legal challenge. Layer on a legal climate where bad-faith suits can stall public projects indefinitely, and you have a recipe for massive documents and hyper-conservative analysis—all in the name of minimizing legal exposure.

In New York, that translated into a 4,000-page Environmental Assessment (EA)—ironically the less onerous NEPA pathway. Producing the EA and its associated processes consumed three years just to assess ten rigidly defined scenarios. Implementing beyond those scenarios—say, altering tolls outside the analyzed scope or incorporating a dynamic target—would likely trigger a whole new round of analysis and approvals. And it’s essential to reiterate that this time and delay has tangible costs. Each year without congestion pricing has meant $1 billion in missed revenue for the MTA, on top of the extra CO₂, pollutants, and societal costs generated by more years of unfettered traffic.

NEPA and similar review processes at the federal, state, or city level are not the bit players they seem—they quietly dictate which ideas even make it onto the table. In my own discussions with transportation engineers, from my time as a congestion pricing startup cofounder, I kept hearing the same refrain: analyzing every possible scenario under dynamic pricing was simply impossible.

But that’s exactly the wrong way around. Dynamic pricing aimed at multiple goals can flip environmental review on its head. By declaring upfront that the congestion pricing system will reduce travel times by X, cut emissions by Y, and improve public health by Z—and then measuring the results and adjusting pricing in real time, that would represent real environmental impact.

Towards More Ambitious Congestion Pricing

New York’s congestion pricing finally launched, and that’s historic. But it arrived saddled with a narrow, single-minded revenue goal, constrained by a labyrinth of political and procedural pitfalls—not least among them, environmental review hurdles that rule out more dynamic, multi-goal designs. If we want implement a system that truly solves for traffic, public health, climate concerns, and transit funding all at once, we first need to rethink how we frame and review these kinds of mega-projects.

In the posts to come, I’ll dig into more opportunities and benefits associated with a dynamic congestion pricing that “multi-solves”, so that New York’s example becomes a launchpad, not one-off miracle, or worse, a cautionary tale.